It Changed My Life: From building bungalows to building a start-up

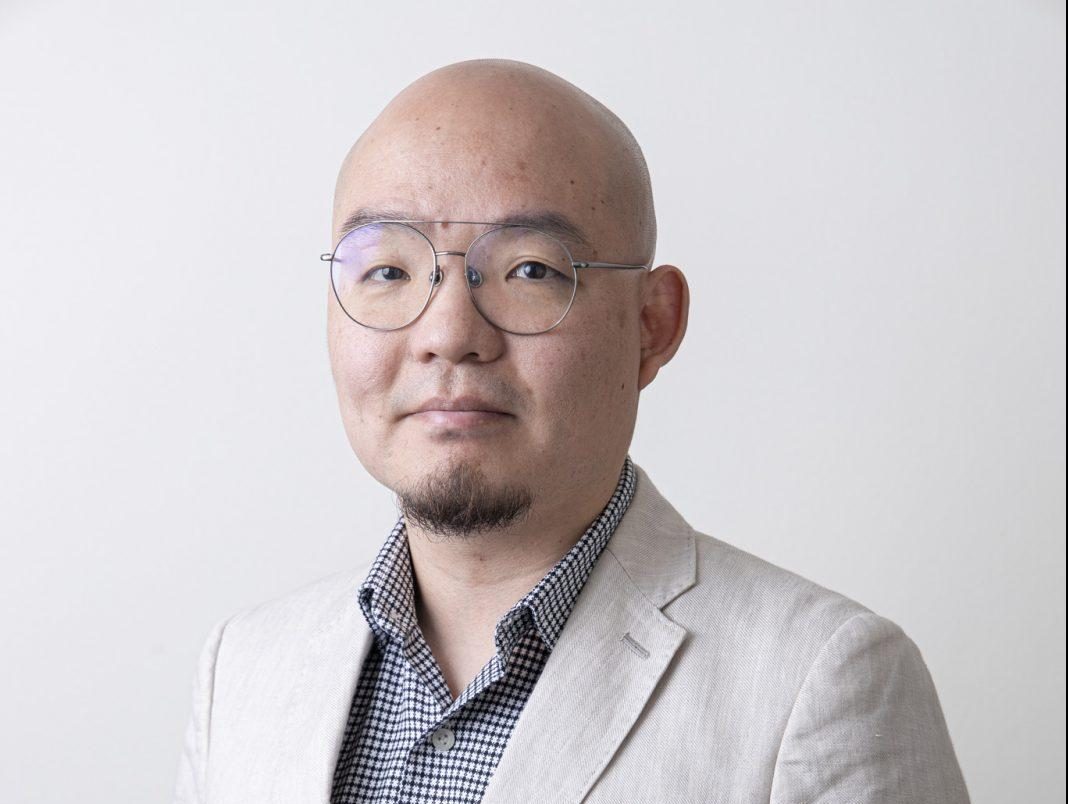

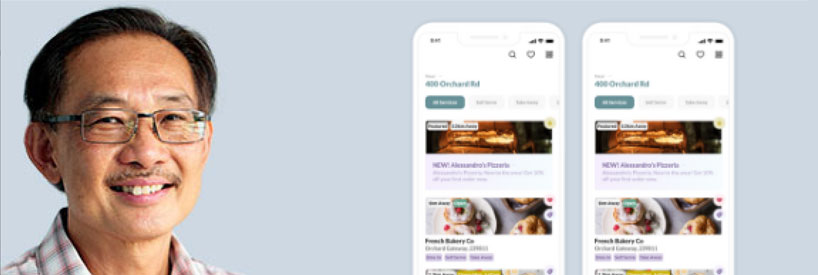

From building and selling a firm and bungalows, George Lim is now into a tech start-up business George Lim looks like your average friendly uncle, togged out in a well-worn cotton shirt, comfortable chinos and loafers. Those who know their watches may notice the only thing betraying him as a man of some means: a discreetly sporty Vacheron Overseas Chronograph Perpetual Calendar on his left wrist. One of only 80 limited edition pieces, it retails for nearly $100,000. Truth is, the 67-year-old is a wealthy man. He didn’t strike the lottery or have an unexpected windfall. He became rich the tried and tested way: through hard work, big smarts and dollops of good luck. He started out in life as a kampung boy, cut his teeth as a technician, put himself through university and worked as an engineer before setting up his own company selling valves and other products for the oil and gas industry. After he sold the business for a pretty penny, he used the money to buy land and build good class bungalows, the profits of which multiplied his wealth many fold. With nice homes here and in Australia, he and his wife could live out the rest of their days in extreme comfort. But resting on his laurels was a decidedly unattractive option, so in 2016, when he was 64, Mr Lim decided to try the start-up life. He launched YQueue, an online ordering and payment solutions platform for the food and beverage industry. Among other things, he hopes the platform will help ease woes plaguing the industry such as manpower shortage, sloppy service standards and administrative inconveniences. The ride has been bumpy because the start-up is operating in a highly competitive space. But Mr Lim is not daunted. He enjoys grappling with daunting challenges. Chatty and congenial, he is the youngest of seven children. His father made a humble living, first supplying nuts, and later curry pastes and pickles, to provision shops and eateries. Mr Lim remembers waking up to the sound of kerosene stoves being pumped every morning as his parents started frying peanuts and cashew nuts in woks. “We’d then help to pack them in small plastic bags before going to school,” he says, adding that the family lived in Tanglin Halt before moving to a house in a kampung in Kembangan. His parents, he says, worked hard to raise seven children. “We were poor but not destitute. Sometimes my father would find it hard to collect payment. I remember him coming home with a cash register one day because one of his vendors couldn’t pay him,” he says. Life was carefree in his kampung except for a brief spell in the 1960s when Singapore was gripped by ethnic tensions. “There was a very tense period in the kampung after a Chinese charcoal seller was killed,” says Mr Lim, who attended three different primary schools – St Joseph’s, St Anthony’s and St Stephen’s. He completed his secondary education at St Patrick’s with mediocre O-level results which qualified him for only a two-year certificate course in mechanical engineering at the Singapore Polytechnic (SP). “It was the first intake. They took in 600 students but only 300 remained in the second year,” he says, grinning. After graduating, he landed a job as a technician with German camera manufacturer Rollei, which was persuaded by the Economic Development Board to set up a production centre here in 1971. Pretty adroit with his hands, he acquitted himself well at the company where he worked for three years. During this period, he took night classes and obtained a diploma in mechanical engineering from SP. National service came next, and he found himself selected for Officer Cadet School. The training, he says, benefited him tremendously. “They put you through training to get the best or worst out of you. I also learnt to relate to all types of people,” he says, adding that the interpersonal skills he picked up were very useful when he later became a boss. In the meantime, he squirrelled away his monthly officer’s pay. By the time he completed national service, he had just enough savings to pay for a one-way ticket to London on Aeroflot as well as a year’s board and tuition at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, where he had enrolled for a degree in mechanical engineering. “By the time I finished my first year, I had shoulder-length hair. There was no money to go to the barber,” he says with a guffaw. During term breaks, he headed for London, where he put in 13-hour days washing dishes in an Italian eatery. The wages were used to pay for the rest of his school fees, and also fund a one-month back-packing holiday in Europe. On his return to Singapore in 1979, he worked for a year in a British marine engineering firm. A friend next employed him to market a valve for the next three years. By then, he was married to a banking executive. Mr Lim’s next move was to set up his own company, Fortim Engineering, selling valves and other engineering parts for the oil and gas industry in 1986. His first office was his home. “I had a few regular customers who would give me small orders,” he says. One day, a supplier told him his boss might have misgivings dealing with someone operating from his home. That prompted him to rent an office in West Coast. There was no looking back after that. The business turned profitable within half a year and expanded quickly. It did so well that he could afford to buy a 6,000 sq ft commercial space to house his operations. By 1999, what started as a one-man operation had a staff strength of 30 and a turnover of more than $15 million. He then sold Fortim “for more than $10 million” to Dutch corporation Transmark, which continued to employ him for the next five years. The sale of his company caused him some anxious moments. While waiting for it to be finalised, he successfully tendered for and paid $18 million for a bungalow sitting on a 48,000 sq ft piece of land in upscale Belmont Road. Homes, he believed, would make sound purchases and offer great returns in land-scarce Singapore. Mr Lim had several sleepless nights when Transmark suddenly wavered in its decision to purchase Fortim. Luckily, it went through with the deal. He later divided the plot of land into parcels and spent $5 million to build three good class bungalows which he sold for a total of $33 million. “I got a kick out of doing that. I really enjoyed it because I could make some money and keep myself busy,” says the enterprising man, who next bought a 44,000 sq ft piece of land in Leedon Road for $24 million before dividing it up to build two houses which sold collectively for about $54 million. In the past 15 years, he has developed and built 15 good class bungalows in Singapore and four in Australia, with several setting sales benchmarks. In June 2018, he sold a newly built bungalow at Jervois Hill for a record $2,729.52 psf. Property developing, he says, is not without risks. He once said in an interview he was 50 per cent leveraged based on the property costs. But he also believes that demand for luxurious homes will continue to grow in tandem with a growing pool of wealthy people. Many of the houses that he has built have been awarded Green Mark Platinum certification, the highest accolade for green features under the Building and Construction Authority’s Green Mark rating system. “I was an early adopter of green technology. I put solar panels, collect rain water, don’t use chlorine in pools. I try to include what I think is important in life,” he says. His own home in Leedon Park boasts an eye-popping 6m-by-4m aquarium. The nest egg Mr Lim has built is big enough for him and his wife to spend the rest of their days taking vacations, sipping pina coladas and admiring the koi he loves so much. But Mr Lim, a permanent resident in Australia where he now spends half of his time, is a man driven by curiosity and a love for technology. “I keep reading about these new things,” he says, referring to tech start-ups. “And I thought to myself it is something that I could do.” In 2016, he decided to build YQueue. The decision to do something in the food and beverage industry is probably driven, in part, by his own experience. He once ran, unsuccessfully, a restaurant in Parkway Parade called Coachman Inn and knows the challenges faced by restaurants, chief of which is the difficulty in recruiting staff. Many operators, he says, also think naively that they will succeed because they cook good food. “But without good staff and good service, the customers won’t come back.” He has several reasons for starting YQueue, chief of which is to help F&B operators tackle labour problems and embrace the digital era. The system that he and his team have developed handles pre-ordering, ordering, self-collection, payment through apps, QR codes and kiosks. Over the past few years, he has poured in nearly $6 million into his brainchild, which he hopes will allow F&B operators to focus on what should be most important: food and service quality. The company employs about 30 people in its offices in the Gold Coast, Brisbane and Singapore. YQueue has more than 100 signed merchants including Subway in Singapore and another 100 in the Gold Coast. About 25 kiosks installed with the software have also been placed in the city and on campuses including National University of Singapore and Singapore Management University. Why not be an angel investor and put money in interesting ideas instead of working so hard in a start-up? Money, he says, is not a problem. “And if it is something I can achieve, it would be nice to have,” he says with a grin. Mr Lim, who does not have any children, wants to spread his wealth around but is still deciding how he should best do it. “I don’t believe in giving money to charity unless it’s a charity which helps people improve themselves,” says Mr Lim who has helped his wife set up a dairy farm employing 20 people as well as a paving factory in Uganda. The way he looks at life, he says, is simple. “If you know there is a way to improve it, you just do it.” Source: